How we conducted and measured D-T fusion

Michael Hua, Director of Radiation Safety and Nuclear Science

Helion has reached a significant milestone on the path to commercial fusion energy production. Our 7th fusion prototype, Polaris, is the first private fusion energy machine to demonstrate measurable quantities of thermonuclear deuterium-tritium fusion and achieve plasma temperatures of 150 million degrees Celsius (MºC).

The team has worked for years to get to this point, and this milestone demonstrates that Helion is ready for high-power fusion operations, paving our path towards the next generation of machine that will bring electricity to the grid.

What is D-T fuel, and why does it matter?

D‑T refers to a fuel mixture of deuterium and tritium, two isotopes of hydrogen. Deuterium is an isotope of hydrogen, the universe’s most abundant element. It is stable and widely available, found naturally in water. Tritium is a rare radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of 12.3 years, significantly less than the half-life of fuel used in nuclear fission.

Until now, Helion has primarily operated with deuterium‑deuterium (D‑D) fuel, and our commercial systems plan to ultimately use deuterium‑helium‑3 (D‑He‑3). D-T is part of our path to fusion power because it allows us to achieve fusion conditions at lower temperatures than with D-He-3 for a given input energy while producing more neutrons with over five times the energy of those created in D‑D fusion. This gives us the opportunity to not only conduct elevated, rigorous standards of radiation safety, but also to validate our physics models, diagnostics, and systems design ahead of turning up the dial for our commercial-level temperatures and fuel.

At scale, D-He-3 is hundreds of times more economically favorable because it produces fewer damaging neutrons, which helps our equipment last longer, and it allows us to reuse the fuel more efficiently. Helion’s unique architecture leveraging pulsed operation, field-reversed configurations, and direct energy recovery enables us to ultimately use advanced fuels like D-He-3, while still using D-D and D-T along the way.

Preparing for D-T operations with rigorous safety review

Before the first D‑T test, our teams completed the critical safety preparations and precision engineering work required for tritium operations. They finalized the fuel modules, validated fuel purity, and completed injector‑performance modeling, alongside finalizing the exhaust‑capture system. A cross‑disciplinary Operational Readiness Review confirmed procedures, safety protocols, and overall system health. With final machine upgrades and diagnostics checks complete, Polaris was cleared for D‑T fuel installation and testing.

Day of testing: The first D-T fusion campaign

On the day of testing, the team cleaned, transported, and installed the tritium fuel‑injection modules under strict personal protective equipment (PPE) and radiation‑safety protocols, and completed installation by mid‑day. Once the tritium scrubber system was placed on standby; the injection modules passed leak checks; and the tritium injectors were tested for consistent performance, we performed routine D‑D pulses to verify machine health before the historic test.

At 5:09 pm, one of our R&D engineers, initiated the countdown for the first D‑T plasma pulse as the team was quietly gathered in the control room. At 5:12 pm, Helion made history. We heard a ‘thunk’ – the sound the capacitor bank makes at the time of a pulse and saw the flash of plasma on the cameras. Within seconds, neutron data confirmed a ten‑fold increase in neutron signal over typical D‑D pulses, an instant record for Polaris. Five additional D‑T pulses followed, some surpassing the first in yield and breaking neutron-production records.

We accomplished virtually all of our inaugural campaign goals on the first day of testing. Each subsequent day of D-T fusion brought new bonus learnings.

Clear evidence of D-T fusion

Helion uses a suite of advanced plasma and neutron diagnostics on Polaris to characterize the plasma, measure temperature (which you can read more about here), and verify when fusion occurs. Several of these tools are specific to deuterium‑tritium (D‑T) operation. Together, they provide multiple, independent lines of evidence confirming that Polaris achieved D‑T fusion.

Organic scintillators: First confirmation of fusion output

Organic scintillators, a tool used to convert invisible particles into flashes of light, are typically the first instruments to register fusion activity. During our first D‑T pulses, Polaris produced so much fusion that our primary and backup detectors saturated, a clear indication of yields far above standard deuterium‑deuterium (D‑D) operations.

By looking at different detectors (we field several to cover Polaris’s dynamic range spanning several orders of magnitude), our team captured clean reaction‑rate curves. The first D‑T pulse produced a signal roughly 10× higher than comparable D‑D pulses, providing the earliest proof of D‑T fusion activity.

Diamond detector array: Identifying high‑energy D‑T neutrons

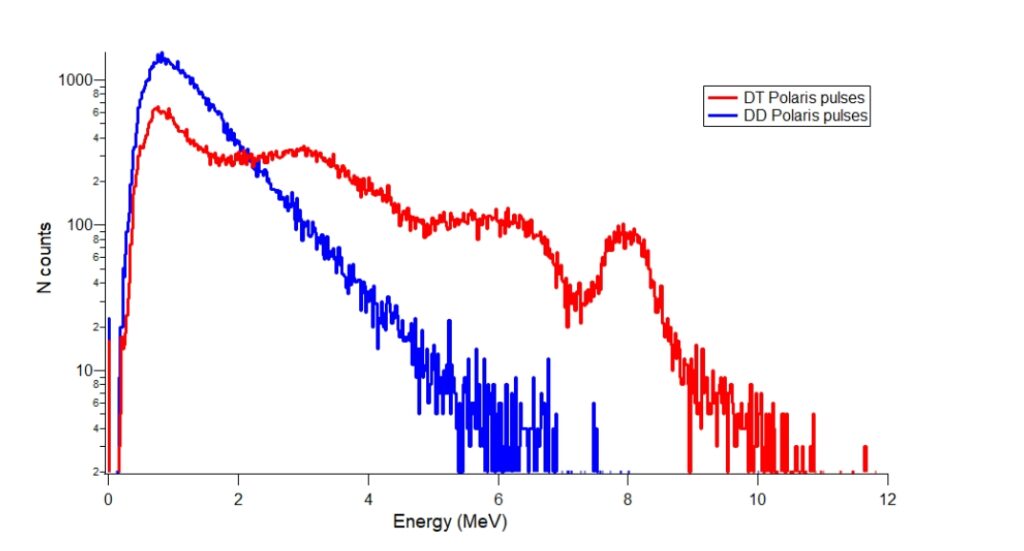

The diamond detector array helps measure exactly what kind of neutrons are produced during a fusion pulse. D‑T fusion produces 14.1 MeV neutrons (resulting in the red peak on the graph below), whereas D‑D fusion produces 2.45 MeV neutrons (resulting in the blue trace in the plot). The diamond array clearly recorded the high‑energy peaks unique to D‑T fusion.

Energy spectrum detected by the diamond array. The blue and red spectra are characteristic of D-D and D-T neutron signals, and the red peaks give us confidence that we achieved measurable amounts of D-T fusion.

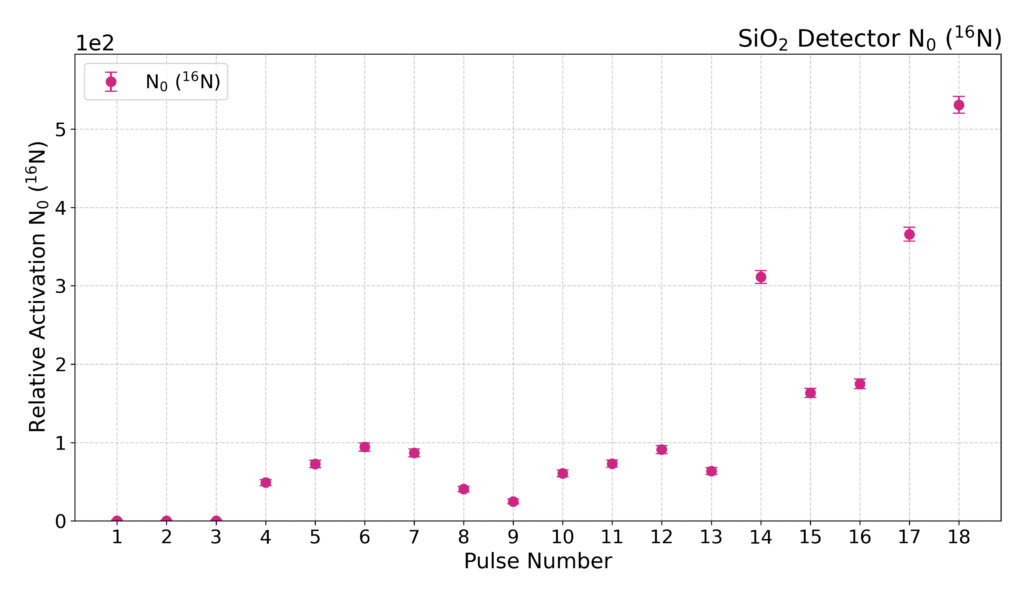

Fused silica (SiO₂) Cherenkov detector: Tracking yield pulse‑to‑pulse

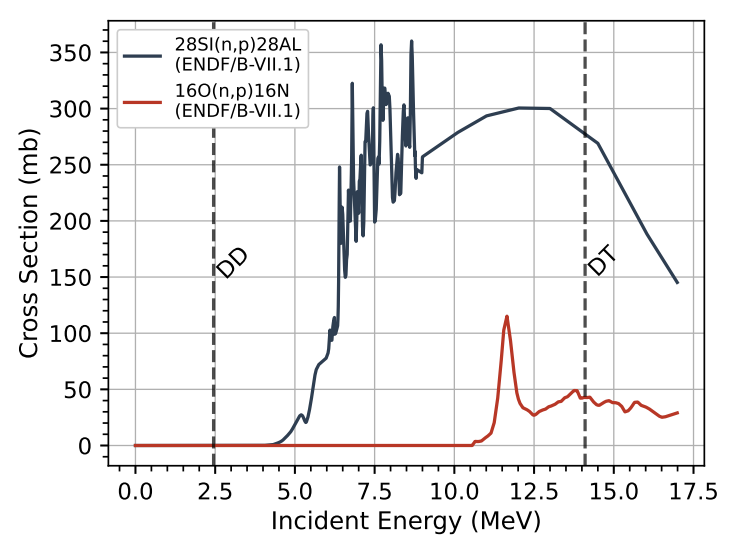

The fused‑silica Cherenkov detector, developed internally and calibrated with support from the U.S. Department of Energy, provides relative yield measurements across pulses. This tool helps quantify how performance changes as operators change conditions. The SiO2 detector is only sensitive to D-T neutrons (see the “cross section” or reaction probability plot below), hence seeing signal in this detector is a clear sign of D-T fusion.

Its data clearly showed:

• A distinct rise corresponding to the first day of D‑T operations

• An additional increase when testing resumed the following day

• Consistent signals with our other neutron detectors, increasing our confidence in measurements

A plot of reaction cross section (or probability) versus neutron energy. The plot shows that D-T neutrons are energetic enough to induce signal in the SiO₂ detector via (n,p) reactions, whereas D-D neutrons are not.

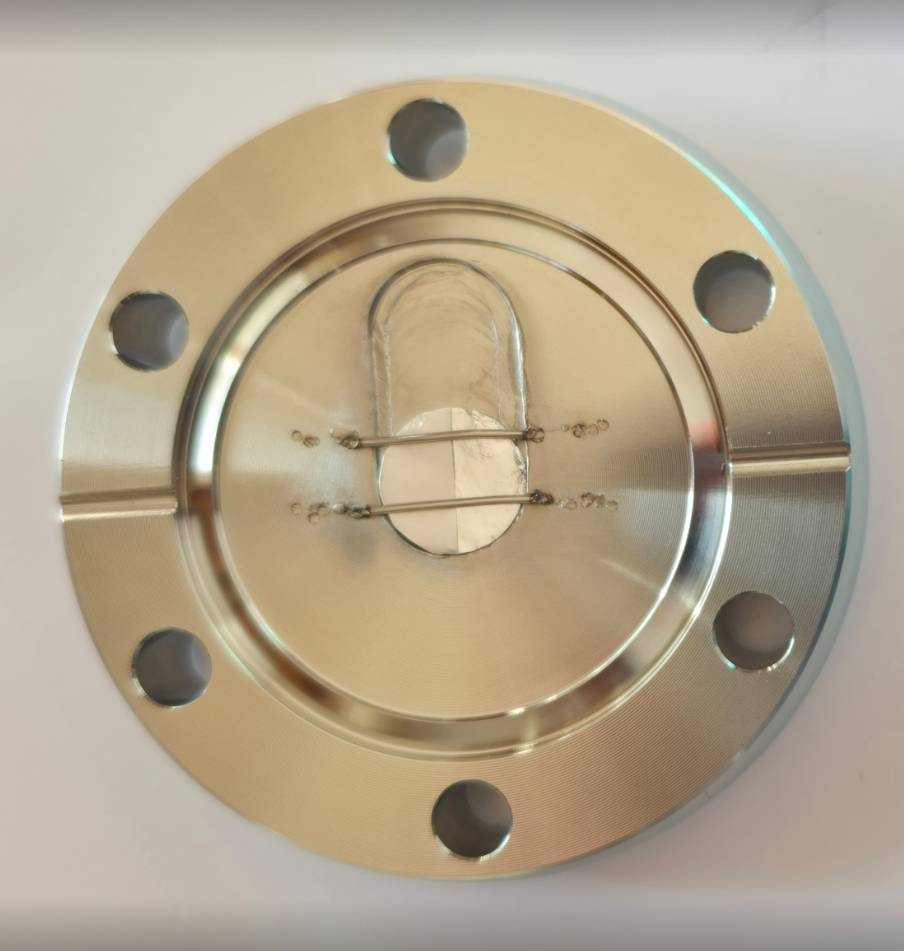

Fast Ion Loss Detector (FILD): Direct observation of fusion products

The FILD diagnostic directly interacts with fusion products inside Polaris using CR‑39 solid‑state track detectors. After exposure, the material is chemically etched and analyzed under a microscope.

Using filters designed to admit only the alpha particles unique to D‑T fusion (3.56 MeV), the detector captured unmistakable signatures of D‑T alpha products. This provided another independent confirmation that D‑T fusion was achieved.

Neutron Activation Foils: Absolute yield

Neutron Activation Foils (NAFs) provide the most rigorous estimate of total fusion yield. Small metal discs are inserted into Polaris during a pulse and later analyzed using gamma‑ray spectroscopy.

Even initial measurements showed activity in copper foils, a definitive indicator of 14.1 MeV D‑T neutrons. Ongoing analysis will refine the exact yield numbers.

What we learned and what it means going forward

Helion’s first D‑T fusion campaign marks a major step forward in our mission to build practical fusion power plants. These results answered several key questions about how our field‑reversed configuration (FRC) plasmas behave during thermonuclear fusion and strengthened our confidence in the path ahead. We gained validated confidence in:

• Our physics models when we transition between fuels

• Our diagnostic systems, which performed reliably even under higher‑energy, higher‑stress conditions

• How FRCs scale as we push to higher pressures and energies

This D‑T campaign also confirmed the work still ahead: forming larger and more stable FRCs, improving how efficiently they translate into our compression section, and turning up our input power and magnetic fields in the compression section to drive more fusion by orders of magnitude.

The next phase is about applying these lessons at higher voltage, higher yield, higher temperature, and ultimately at the scale of Orion, bringing us closer to scalable, commercial fusion energy.